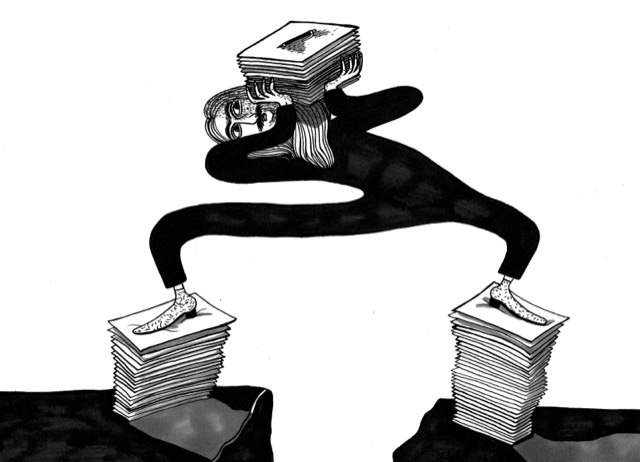

Kabul-born illustrator Moshtari Hilal did this drawing to accompany my article in Unbias the News. I am using the drawing with their permission.

Lorenzo was born nine months ago, on a Tuesday evening, 10 days earlier than the expected date.

On the Monday night, unaware of what was about to come, I was up until 1am finishing a translation for a story I was producing. I was catching up on emails and sending invoices. I could feel that I had to get things in order before the little one arrived – and unlike my doctors, I had a feeling I had little time left.

I went to bed at 1.30 a.m., and contractions started shortly after, around 2.30. When I was 100% sure I was having proper contractions, I wrote to a couple of editors. I was due in for my editing shift at Worldcrunch that morning, plus I had a piece to hand in the following week. I told my boss at Worldcrunch the big day had arrived and I would not make it, and asked for a one-week extension for the other story. I eventually went into hospital around 4pm.

Lorenzo was born at 9.28pm on 12 February. It was a natural birth. The pain and tiredness was insane, and I had no choice to get any painkillers or to be in a birthing pool, but you’ll hear more about that story another time.

The point is that the following day, 13 February, I was on email, and I added this out of office reply: “I have just given birth to Lorenzo, so I am not reading emails that often. But no worries, I am not on maternity leave. Because that is something we freelancers do not really have access to.”

After freelancing for 15 years and living in over 10 countries over the past two decades, my tax situation did not give me access to paid leave. Plus, I am married to another freelance journalist, and we don’t own property. So, could I really turn down potential clients knocking on my door? Which is why I was clocking in work hours from my hospital bed and fully operative already by the following Monday, when Lorenzo was six days old.

In many ways, I was lucky: I was well and fit after giving birth, got no stitches and had great mobility, plus I had a partner working from home who could be there constantly to figure out how to put a diaper on. Breastfeeding was painful but eventually worked, relatively quickly. What’s more, Lorenzo was quite a good sleeper, and, maybe more importantly, healthcare in Italy, where I gave birth, is free.

When Lorenzo was two weeks old, I was heading home, thirsty and tired, after a paediatrician’s appointment followed by a walk uphill in the sun. When my phone rang, I wasn’t expecting to be talking to an editor. But there she was, down the line, asking for a live TV interview the following morning at 7.30am. I had hardly slept the night before because exclusive breastfeeding meant that Lorenzo had been attached to my breasts for most of the night. Appearing on television the following day to tell viewers the latest on the Italian economy seemed impossible from where I stood.

Not knowing what to tell the editor, I was honest: I explained that Lorenzo was born two weeks earlier and I had to sort out some logistics before committing. She seemed unfazed by the news, as if I had told her that I had to check my internet connection first.

By the time I had made up my mind that I would try it out – because they might not call me again, and being a mother does not mean you cannot work anymore – the editor wrote: “Unfortunately I have to cancel.” She said they would not need me after all.

The exchange with the editor made me angry, but also got me thinking. For years I struggled as a freelancer, but I loved the work and if I earned a little less, then all I had to do was adjust my expenses. But now, with a child, could I afford to be a freelance journalist? And can anyone really afford to be one – often having no access to a regular salary, maternity leave or holiday pay, while earning as little as $25,000 a year? If only a few can afford to be freelance journalists and the journalism industry is so exclusive, what does this mean about the news we produce? Is there a bias that results from these conditions?

I asked all these questions as part of an article I wrote for Unbias the News, a book on why diversity in journalism matters, edited by journalism network Hostwriter and non-profit German newsroom Correctiv.

Now that I am in the privileged world of having a stable income, I’m repeating those questions, expanding them far beyond journalism. What does it mean for the wider world if new mothers are not given the option to have paid maternity leave? Who can really afford to become a mother, and what actually is the cost?

These questions are not new – and there are plenty of studies out there about the so-called motherhood penalty.

I would love to hear from you. Have you or child carriers around you not had access to leave after giving birth? How did you/they cope? What does motherhood penalty look like to you – or to those around you?

Until next week,

Irene

P.S. Following last week’s newsletter where I spoke of native language(s), I received a very nice email from member John Chew, who pointed out that my wording was excluding a lot of people who have more than one native language. Thanks to his suggestion, I updated the newsletter and added a correction at the bottom. So, do send me a message if you think my writing is not inclusive. I look forward to learning more from our exchange.

This article first appeared in The Correspondent, the member-funded platform that shut down on 1 January 2021.