If you’d met me some 30 years ago, you would have found a rather opinionated child, somewhat chubby after early puberty, with a passion for 1960s protest music, flare jeans and the colour purple. I held opinions on the latest political crisis in Italy, spoke up against inequality, read everything I came across, wanted to speak other languages and hang out with adults. As I think back about how odd a child I was, I find it hard to distinguish which traits were my own and which were a result of my family’s oddness. Just to give you an example, my parents met at a political meeting in the 1970s when my father, a Trotskyite, was a trade union leader, and my mother was politically involved with the student movement in Naples. Politics was a staple at our table, even more so when my parents had friends over. Was I interested because it was readily available for me? It’s hard to tell.

It goes back to the good old debate between nature and nurture: which are the characteristics we are born with, and which are the ones we learn from our environment? Even when it comes to the sex you’re born with, there is a huge controversy as to how much it really conditions you in one way or another, as I wrote about in one of my pieces last year. Of course the nature-nurture debate is even more complicated, because it turns out that eve our genes are affected by our environment, but – quite honestly – I am not going to get into this conversation because I am not an expert.

I find myself thinking about nature a lot these days when I sit around with Lorenzo, my son, who is about to turn two years old. Is there anything that I can infer from what he does these days about his future, about his inklings? Is his current obsession with crayons just a childhood pastime, an appropriate developmental stage, or is there more to take from it? How much are Nacho and I, his parents, affecting his attitudes? And also, why am I always projecting my son’s life in the future?

A room of my own

I have the honour of writing this newsletter from my very own office. When we decided to settle in Greece for a year, I was clear that I needed to have my own room. During four years of being nomadic, house sitting and living with friends, I worked from beds, kitchen tables, out of cars and trains, always longing for a space to call my own and go back to every morning. Having a room of one’s own is a tremendous luxury, one that Virginia Woolf said helped her marriage and made her writing possible in the first place. I couldn’t agree more, especially with a loud toddler around the house, having a (for now off-limits) sanctuary makes life easier.

But thinking back about my own space, I didn’t have my own room until I was 16. Even then, in the flat that my parents had struggled for years to get renovated and fixed up, I had a relative choice of what to do with my space. No posters were allowed on the walls unless they were deemed worthy and framed and hanged by my dad. The clear understanding was that the freshly painted white walls could not take any scotch tape or other violations to their pristine nature.

To be fair, I never really longed for my own room growing up. Throughout my childhood, I shared a room with Mauro, my brother, who’s two years younger than me. Our room fit a single bed (mine) and an armchair bed (his), plenty of shelves for books and a big antique wardrobe with a mirror, with a matching console table. At some point the room also hosted one of those old-school computer tables with sliding trays with our father’s first PC, from back in the 1990s. On the walls there were bits and pieces from my parents’ overflowing collections of objects they would buy around the world. There were some West African wooden masks, mainly Dogon and Senufo, that used to scare my brother when he was very young because of their hollow eyes. Mauro and I lived in what my parents had carved out for us. Slowly, in a sort of subconscious revenge, the two of us began taking over the whole apartment, scribbling in bright colours over every single wall, as high as we could reach – something that my lover-of-pristine-walls engineer father abhorred but did not know what to do about.

When I think about that room, the only one I called my own for an extended period of time, one of my favourite things about it was that I shared it with my brother. Growing up with him made it easier to be myself. There were things that he liked that I didn’t, like playing his own version of Subbuteo, a tabletop football game with miniature footballers which we would flick with our little fingers, with a complicated scoring system and very detailed tables that he would write down. I was verbally manipulative and bossy. He was quiet and rebellious. He would pick up the book I was reading and read the final page out loud to me in an act of sabotage. I would lecture him on all of the things he could do instead of playing Subbuteo, like read a book, of course, or play with my Barbie dolls with me. But what parts of these recriminations were just in reaction to my brother, and what parts were just my own instincts?

I loved being in the water for hours, coming out only when my mother would start shouting for me, or when my skin was so wrinkled that I would hesitate, worry. But for a long period of time, Mauro didn’t like the sea. If we approached the shore he would kick up a fuss and run away. Mauro had started disliking the sea after he was caught in a tangle of seaweed on the shore one summer when he was three, somewhere in Turkey. He eventually became at ease with the sea again, but for as long as I could I would tease him, going straight for his manly pride: “Are you afraid of losing your willy?” I would pick on all the best assumptions that patriarchy had ingrained in my young psyche. I now know that my provocations came because I felt lonely without him in the water. So I overcompensated by jumping from rocks and throwing myself head down first, pushing the boundaries all I could.

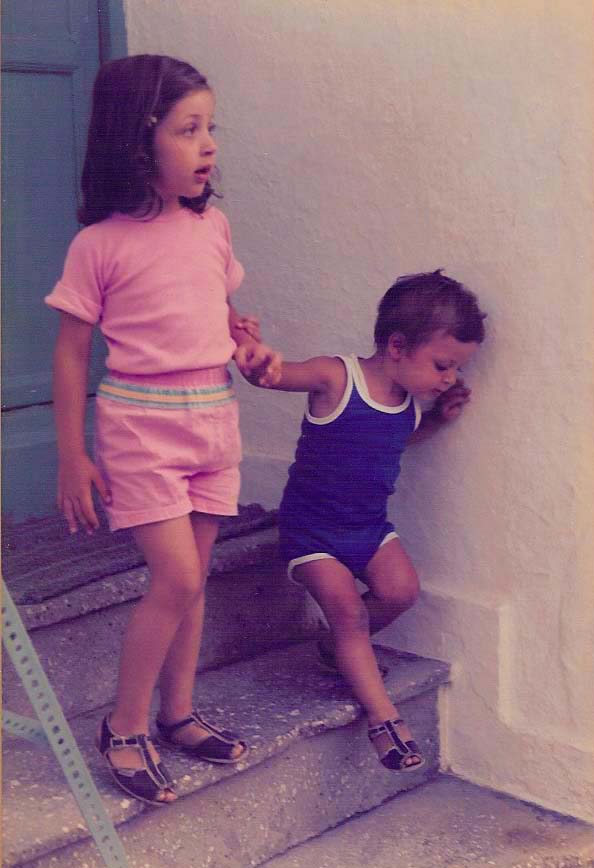

Mauro was (and still is) different from me. One photo, one of the most infamous in our family album, illustrates his personality best. My father took it in Greece in the same summer of the seaweed incident. My brother and I wore the same shoe brand, the iconic blue Chiccos that all Italian kids wore in the summers of the 1980s. We’re on a staircase. I look ahead, towards the horizon, my body seems ready to spring into action. Mauro, still wearing his diaper, leans against the wall with one hand and holds onto my arm with the other, looking down, reaching a tentative foot out, evaluating whether or not to go down the step.

Did we live out the expectations set by that family picture, of me, the responsible elder sibling, protector, carer, and him, uncertain, unsteady, carefully taking a step forward? Years later, it turns out that I am the one with a financially unstable career, while he is a professor of economics with a savings account, who is about to buy property in Italy.

Sometimes I wish we could let go of all these labels and go back to hanging out and playing in the same room, or on the beach. Grown-up conversations get in the way of love sometimes. Next time we are in the same city, I will make sure to organise some play time amid the grown-up duties, and see where we stand, all these years later.

Over to you: What were you like as a child? What qualities did you have back then that you’ve kept? I’d love to hear from you. You can get in touch by replying to this newsletter. Next week, we’ll launch a website where paying members can log in and have a conversation with others. In the meantime, fill my inbox with your stories!

And now, a confession. It’s been a difficult week and I’ve been laying low. The following tips are an honest reflection of my shrinking bandwidth this week.

What I’ve been reading

I’ve been reading emails from former members of The Correspondent, many of whom are now part of this community. I found encouragement, some praise, some corrections, a lot of tips and ideas. But what I love most is how much you readers have been willing to share with me. This is already happening in these early days of The First 1,000 Days, and I want to thank you all for being in my inbox, because it makes my writing worthwhile. One of the best tips this week came from Joram, who told me about children’s cooking towers, a really simple wooden structure that allows children to stand with you at the stove or as you chop, overseeing the process of cooking without risking a fall. Something like this.

What I’ve been listening to

I’ve been trying to listen to my breath. I found that it helped me feel more settled when I wasn’t, and it also helped me put my son to sleep one night. If you’ve never done yoga and want some tips on how to listen to yourself breathe, I am loving doing Texan instructor Adriene Mishler’s free yoga course this January, here. Try it if you have a spare 20-30 minutes, and try to work it in your daily routine for a month, as she guides you!

What I’ve been watching

This video of a small toddler, over and over again. Check out how she is making sense of the world in times of coronavirus by looking for sanitation gel dispensers everywhere, at her height.

Who’s been inspiring me

Two of my former colleagues from The Correspondent have been so instrumental in my being able to launch this newsletter and to keep it coming week after week. They are also part of The First 1,000 Days community, and I want to let them know how much they inspire me. First, Nabeelah Shabbir. No day goes by without her sending me a link to something relevant to my writing, or a sweet note checking in on how I am. Yes, she was the conversation editor at The Correspondent, but titles are what they are, just a label. She is great at experimenting and bringing people together. If you want to hire her, these are her details. And now to Imogen Champagne, with whom I share initials, even though I’d so much rather have her cool surname! She was officially our engagement editor, but she did so much more than writing our newsletters and managing our campaigns. She’s a brilliant editor, has a great sense of what is a story and recognised my voice before I even knew I had one. You can find her details here.

What I’d love to hear from you about

If you’re interested in helping me out more actively with this newsletter by proofing it, or by commenting on it before publication, please let me know… I’d love to take you up on that!

See you next Wednesday!

With love and care,

Irene